PAN YI CHENG

Company name

Produce Workshop

Company Year founded

2013

Name of Founder(s)

Pan Yi Cheng

Founder Birthdate/year

06.02.1980

Education

Diploma (Hons), Architectural Association

1st Job

Architect, UNStudio

Other Pursuits

Type0 Architects (2018)

Other Pursuits

Superstructure (2017)

Location (current office)

66 Kampong Bugis (Produce+Type0)

Period of Occupancy

2 years (and ongoing)

Space (Produce+Type0)

2270sqft

Number of Staff

12

Location (current workshop)

22 Sungei Kadut Ave (Superstructure)

Period of Occupancy

2 years (and ongoing)

Space (Superstructure)

2000sqft

Number of Staff

10

Location (2nd Office)

22 Sungei Kadut Ave

Period of Occupancy

2017 (and ongoing for Superstructure)

Space

2000sqft(studio) 2000sqft(workshop)

Number of Staff

Produce(9) Superstructure(7)

Location (1st Office)

1007 Eunos Ave 7

Period of Occupancy

5yrs

Space

500sqft(studio) 1200sqft(workshop)

Number of Staff

6

2001

Left Singapore for UK to study at Architectural Association

2006

Graduated with Honours from Architectural Association, joined TP Bennett(UK) as architect

2008

Left TP Bennett, and joined UNStudio(UK) as architect

2010

Returned to Singapore

2012

Herman Miller's shop-in-shop at Xtra Park Mall won Best Retail Building at World Architecture Festival 2012

2013

Founded Produce with 3 partners, a studio with workshop space

2017

Herman Miller's shop-in-shop at Xtra Marina Square won World Interior of the Year at Festival of Interiors 2017

2017

Produce moved to Sungei Kadut and co-founded Superstructure with Emily Sim, focusing on computational design and digital fabrication

2018

Founded Type0 Architects, an outfit focusing on architecture

2020

Produce, Type0 Architects and Superstructure showroom moved to Kampong Bugis, with their workshop space remaining at Superstructure at Sungei Kadut

The Digital Craftsman

By Elaine Chan, 31 January 2022

Can you tell me about Produce? Why and how it came about, and how it has evolved?

Produce started in 2013. I’ve just, at that time, gone out of another partnership which was called PAC. It was a company focusing on masterplanning in China I had been in, as a partner in that company, which I started with a friend for the past three years before Produce started. However, this project in China, it’s too large and speculative. After three years, nothing was built and I had kind of an urgency within me to get something materialised. So I started Produce in 2012 with a few friends but mainly focused on design and make.

We wanted to be able to make small things. So from a big masterplan that we couldn’t realise, or at least I couldn’t realise, I wanted to start from very, very small objects, even furniture, I don’t mind, just to materialise them. So we got hold of a CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machine – three-axis CNC machine, and we took over a workshop space in Eunos. We had our very small team, I think just three of us when we started, three designers including myself, and then we were on the second floor and we had our workshop on the first floor, or ground floor.

With that CNC machine, we began doing very small projects, such as a feature wall in an HDB house, and then, we were also working on a restaurant called Wild Rocket. That was actually quite an important project because that then led on to Kki, which is another restaurant and other interesting retail and commercial projects.

Produce became a design and make studio, partly as a retaliation to the kind of lack of craftsmanship in Singapore. At that time, I also completed [the first] Herman Miller at Xtra Park Mall – this parametric structure was entirely produced from CNC cutting.... just before I set up Produce. We did not have a machine then, and it was then outsourced to China. And I quickly realised that in Singapore, there was not enough competition to drive the price down. And it became very expensive to produce this in Singapore. We even managed to do a 1:3 mockup that was done in the UK at almost half the price, compared to Singapore. Having had that experience and realising that we need very rapid kind of prototyping processes to realise such projects, we decided to get hold of our own CNC machine. So Produce, basically, was born out of my desire to materialise some of our concepts, ideas, but at the same time, it was also a desire to kind of model the studio like a school environment where we can quickly go downstairs to the workshop and do up a physical model to test the viability and feasibility of our ideas very quickly.

Since 2013, we have won a number of projects particularly in this kind of computational and parametric work. And then in 2016, Xtra Herman Miller re-engaged us because they had to move to Marina Square. They basically told us to do a second version of the Herman Miller pavilion. And this is where all our practice since 2013 culminated in a very interesting structure made of 2mm plywood which is still now in Marina Square. So that won us the 2016 interior design of the year at the World Architectural Festival, that was one of the highlights of Produce until now.

Produce became a design and make studio, partly as a retaliation to the kind of lack of craftsmanship in Singapore. At that time, I also completed the Herman Miller at Xtra Park Mall – this parametric structure was entirely produced from CNC cutting.

Is this set up quite unique in Singapore?

Yeah, it is actually. I believe until now we are still only the design practice with our own prototyping facility. Actually it’s not that uncommon from where I graduated, which was London. There are many very small studios that invest in a little bit of their own workshop space, even very famous names like Ron Arad, they have their own workshop space. And Herzog & DeMeuron, when they just started out, they also had a yard where they could kind of test out materials, test out different effects on materials. So I think from my experience abroad, I thought that would be something that is most, I guess, straightforward in terms of translating an idea to reality. And we adopted that as a practice. I think that is quite interesting, I guess, in addition to our current industry in Singapore.

And we are growing right now. In 2017, after we won with the Xtra Herman Miller [project], I decided to make the workshop a separate entity from Produce. I partnered up with Panelogue which is run by Emily Sim, and then we started Superstructure. Superstructure right now as a separate entity focuses on digital fabrication and works with different architects, contractors, artists, to translate the designs or concepts into reality. Right now, Produce and Superstructure work hand in hand on some unique projects. I think yearly we have two or three interesting projects we work on together. Otherwise these two companies are basically separate entities.

Produce was born out of my desire to materialise some of our concepts, ideas, but at the same time, it was also a desire to kind of model the studio like a school environment where we can quickly go downstairs to the workshop and do up a physical model to test the viability and feasibility of our ideas very quickly.

What is your focus like? How much time do you give each side, or do you look at it in a holistic way?

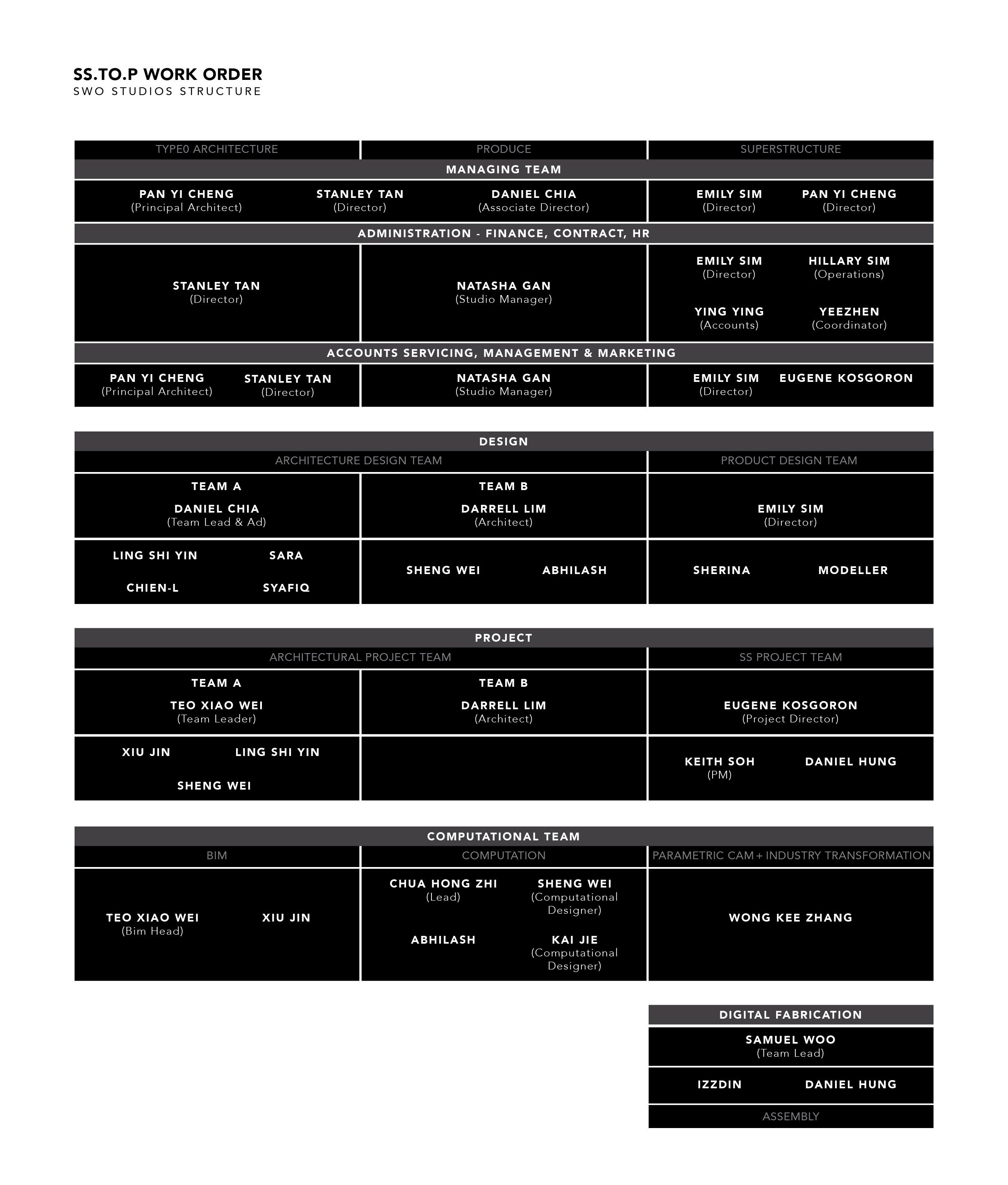

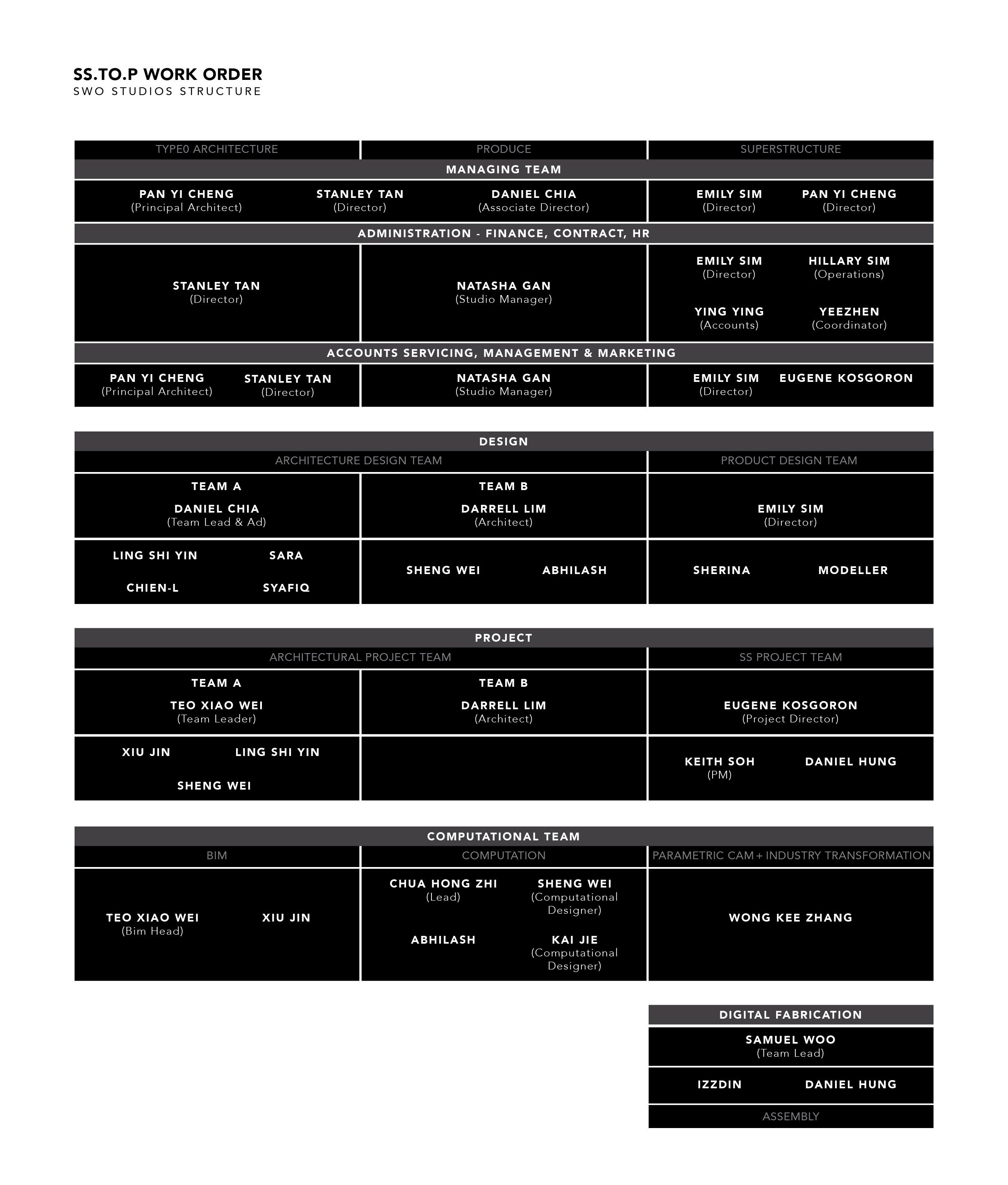

I try to look at it holistically. There is a team that I set up that stretches across all my three companies. By the way, I also run Type0 Architecture, which is an architectural firm. So this team that runs across the three companies is the computational team, and within the computation team, I have BIM as one of the departments. I have the computational scripting department as well as the CAM, which is the translation of a computational file to a fabrication file. So within there, this is where I still control, in a way allow the three companies to function very integrally. And that is where the knowledge of the three companies – whether it’s in computation, in technology, material or even in content – is archived within this computational team. So it’s like a knowledge base where we are constantly accumulating and building up

What inspires you? Who and what influences you?

I think it is a difficult question. I mean I…

At least in this moment of time? Or this stage of your career?

I very much look up to people who are pushing the boundaries, whether architecturally or in terms of technology. I look up to figures like Elon Musk for example, who are kind of first-movers in his own field. That inspires me a lot. And what it says to me is – there is a problem at hand that everyone can see. And basically with the skillset we have, how can we best structure ourselves to contribute to solving this problem.

Every time we come up with a problem statement, I would kind of re-organise the company, set up a team, and then look towards – not solving it – but at least contribute towards addressing some of these points. For example, we have been talking about climate change, sustainability issues for so long. Before the pandemic, I remembered, this mass engineered timber solution had been around, even for decades. But it only became very, like right now [prevalent] during the pandemic. So instances like these push me and the company forward because we have the skillset and we have the machinery to at least address part of this issue. Right now, we are actively looking at experimenting with mass engineered timber using regionally-sourced plantation timber. So at least … We don't say we can solve this issue, but we want to be the first-mover in starting this change. There are some very big ideals and goals that from time to time, we, me and the team, put on the table, and it helps to drive us forward and give us a sense of hope.

Every time we come up with a problem statement, I would kind of re-organise the company, set up a team, and then look towards – not solving it – but at least contribute towards addressing some of these points.

Apart from sustainability, are there any big goals that you’re looking at right now? Or other common themes?

The other common theme is, it’s actually quite linked to sustainability. It’s the whole idea of the Fourth Industrial Revolution where different technologies are collapsing, kind of consolidating more and more, and integrating more and more with one another.

I mean the entire industry requires a lot of integration, particularly the construction industry which is actually a very fragmented one. And that leads to a lot of problems, not just in sustainability, but in productivity, in social mobility, and so on and so forth. Also, as a profession, the architecture profession, it cannot be struggling behind in terms of the progression of the technology and the whole industry. This is something that we are also actively focusing on, to digitalise and see how best we can combine all the systems and integrate them within our workflows.

The technological production started the architectural movement in the 1900s, because of the Industrial Revolution. At that time, steel just became a new building material that enabled all the high-rises. I believe we are at the brink of the next architectural revolution but this time, it will be within the control of the architect because we are – with our skillsets, we can actually integrate a lot of processes and then production no longer will become something that limits the architects’ creativity. Because it used to be the architects using whatever that is available in the industry, but right now, we are at this moment where we can design tools, design machines to produce what we need, to start off a whole process with this digital revolution.

Once again, I think the control is back in the hands of the master builder, also known as the architect. Hahaha, it is the original definition of the architect! Just that over the last 100 years we’ve outsourced so much of our expertise to different parties. So it’s actually quite exciting. I believe that with that, we can affect the entire chain, what I call the means of production of architecture. Which is from creating knowledge, being able to affect how we source for material, how we process the material, and then we can affect how this material turns into structure, how we use as little material as possible to achieve the structural requirements, and then right down to how we document and realise this project. So the entire chain, the entire means of production of architecture, is something that I feel needs to be led by the architect. Or at least be influenced by the architect.

The construction industry is actually a very fragmented one. And that leads to a lot of problems, not just in sustainability, but in productivity, in social mobility, and so on and so forth. This is something that we are actively focusing on, to digitalise and see how best we can combine all the systems and integrate them within our workflows.

I’ve read that one of the questions you think about is how humans live and that guides you in your design work. What is your design philosophy and what is the design process like for you?

I like to search for the existential crisis, the existential crux within every project. Even actually, the way I look at myself and how I live in this environment in Singapore, and then in the world. I look at it from a very existential point of view. Particularly, I want to know, and fundamentally, why we exist on this earth. That’s something I’m interested to think about…this metaphysical existence. So I tend to search for so-called, the essence.

In architecture…I studied typology, so we look for the deep structure of a building, basically it’s the central idea and the main important point of the building. Without it, everything as a building, it fails. So that’s how I approach every project. I want to know how this project comes about, and through the analysis, which is contextual – it can be about the site, about the client’s personality and it can also be about how the client acquired that piece of land. Because that makes up the crux of the situation and how this project comes into existence. From there, I, normally… in such a case, there is a certain kind of conflict, either within the project or without the project, that means from the point of view of the project vis-a-vis the surrounding environment or the surrounding context. And that’s how I normally derive a narrative and then a strategy towards that. So if I have to sum it up, I guess I still look for what is essential or what is the form of existence of the project.

I like to search for the existential crisis, the existential crux within every project. That’s something I’m interested to think about…this metaphysical existence. So I tend to search for so-called, the essence.

Earlier on you mentioned a few critical projects that actually shaped the development of produce. Are one or two [other] projects that you can tell us more about that’s definitive and representative to you and also to the studio?

It will have to be the second version of the Herman Miller pavilion within Xtra. This is a project where I think every facet of the process is so intertwined, interlinked and it reaches this level of fitness which I really sought after; I don’t like a lot of different veils within a project. To me, I look for the one-ness, or the wholeness in the project.

So for this project, it started off with trying to understand plywood as a material and how do we most economically use plywood. It comes in a sheet, 4 by 8 feet – and how do we maximise this sheet without having to cut it into smaller pieces. I started by looking at how tailors shape cloth, through a process of darting to fit it to the human body. I thought that could be an interesting idea to export it onto plywood.

It became a process of designing this technique to tailor plywood to fit a particular form. The technique then results in a very unique undulating form, that is only possible with this technique. And with this technique, there are also holes that I needed to create to relax the plywood such that it doesn’t break. The holes are also signature to the texture of the entire structure. From there, the material, then the technique, and then the entire expression of this technique into a form – it is continuous, it is not something that can be broken, taken apart, and still function as a whole.

This entire process was borne out of our research into Herman Miller, looking at Eames furniture which was one of the most iconic pieces of Herman Miller furniture. They use a moulding process to shape plywood. And I asked myself – how could we do this at a large scale? It’s possible to do it at a furniture scale? But at a large scale it’d be too costly and not economical at all. So the entire process became a question of how then can we shape plywood? Which was kind of a continuation of the question that Eames was asking – how do we make furniture, how can we mass produce timber furniture? At that time, there wasn’t any moulded plywood yet. They took this from … during the Second World War, they used plywood to brace a broken leg, as a leg splint. And that became a technique that they imported to furniture. This whole narrative really inspired me. He was the first mover in that sense. And we jumped into this process, looking and experimenting into plywood, believing that we could actually come out of it with a different technique, and luckily we did! And I think that’s really something – it’s a very important moment for Produce, because that is the level of finesse that I wish to achieve, at least for all of my projects, if I can.

What’s next for you? How do you visualise your design going forward or what are your aspirations?

We are hopeful that we can do larger and larger projects right now. I’m also currently involved in master planning the Paya Lebar airbase with a team of architects. You know I left the master planning bit of practice which I set up with my friend called PAC, because I needed to realise things from the bottom up, like from small to big.

At this moment, I really hope that the next five years will…I can get back to doing at least more urban type of projects. The way I see it is that – there are always smaller parts that come together to fit into a bigger whole/home. Like how fibres of timber come together to form plywood and how we use the technique to create that structure. Likewise, the city is also made up of smaller grain material, it’s a single building, a single household, it’s a single inhabitant, so actually I think it’s the right choice to go from small…because I started to see from an individual household, an individual citizen’s point of view, on how living in a city is like, or how one exists within this city called Singapore, or any other city for that matter. Looking forward, I’m looking at larger projects like mass housing. Currently, we only have [worked on] landed houses but we are hopeful that we can get more mass housing projects in the future. Maybe in Vietnam or other regions.

And then the whole question of how we exist as a civilisation is something that I hope to work towards in the long term, and what kind of aggregation of individuals is possible. How do we organise these entities or as you call them, minimum building blocks of the city, in a way that is most equitable, is most free…that gives more opportunities to different stakeholders within the city. That’s a central question that I had – and I always have – since I graduated from the Architectural Association, which is about the freedom of the urban plan. That is something that I feel right now, and I am starting to ask this question again. If I get larger projects, I can really investigate this matter.

And then the whole question of how we exist as a civilisation is something that I hope to work towards in the long term, and what kind of aggregation of individuals is possible.

Would you say that the timing is ripe, right now for you to get back into masterplanning versus pre-2013? At a personal level?

I felt that I would not be here … I mean currently, the kind of setup that I have I would not have imagined it, if in 2013 I had continued to go into masterplanning, urban planning. I would not have ever imagined myself doing digital fabrication, computational work; all this wasn't even something I actively pursued, before 2013. It was a very, very, very different way of practice. So I’m thankful for whatever has happened and the people who have helped me along the way, setting up Produce especially. I can’t say if I have continued my way in 2013 where I would have ended up but for sure, this current setup is never what I would have imagined.

You earlier alluded to the appreciation of craftsmanship and also craftsmanship in Singapore. What do you think, in your view, can be done to elevate that kind of appreciation and the skillset that craftsmen have?

So this is the question I had when I started Produce. I felt that there is a lack of craftsmanship. We were at Eunos; it’s a very old industrial estate. The craftsmen around me were all ageing, some of them almost turning blind, and were retiring. It was very difficult to even do something out of the ordinary, as they were quite used to their old ways.

I started to question if there was still craftsmanship in Singapore and what is Singaporean craftsmanship for that matter. And then I see people doing projects using rattan and bamboo and that takes a lot of effort and difficulty in doing these projects. They are very labour intensive and this labour is never paid well. It is counter-intuitive to the environment that Singapore had been in since the 1960s. That craftsmanship had been phased out over time because we had outsourced a lot of our manufacturing overseas.

When I asked what is Singapore’s craftsmanship, I believed that we need to start from scratch. If I am not going to be doing it with my bare hands and start carving wood and all that, then what can I do? I believe what we need to do is to use more efficient ways where we rely less on craftsmen and use machines to aid us. So I see more of ourselves as craftsmen with machines, with the tool, these digital tools that we have. I think craftsmanship … we can then start to talk about what local craftsmanship is like. It has to be borne out of means that’s available to us. When it becomes so labour intensive and hiring labour is so difficult , and you don’t want to pay the levy for foreign workers, then you’re left with very straightforward options – to adopt digital fabrication or doing something more simple. I refuse to take the latter route because I think with digital tools now so democratised, everyone can go buy a CNC machine, desktop is not that expensive, and now everyone can afford a 3D printer. It’s definitely something that everyone can start adopting and start building up – what we call local craftsmanship. And it has to be borne out of the means of production, and not out of nostalgia of the region. We cannot take something from Indonesia and call it Singapore craftsmanship. That I think is important, to be true and authentic to the project and our practice.

I believe what we need to do is to use more efficient ways where we rely less on craftsmen and use machines to aid us. So I see more of ourselves as craftsmen with machines, with the tool, these digital tools that we have.

What kind of books do you read and what are you reading now?

I read all sorts of books. I read philosophical books. I like novels that are romantic in nature. I mean romanticism, not romantic novels. I like novels from Ayn Rand, I have almost all of them, all of her books.

Recently, I’m reading about geopolitics, reading about ASEAN and the trade war, like problems of geographies, in Russia, and different parts of the world. I’m very interested in how ASEAN will be in the next decade, and I’m reading books about coding as well.